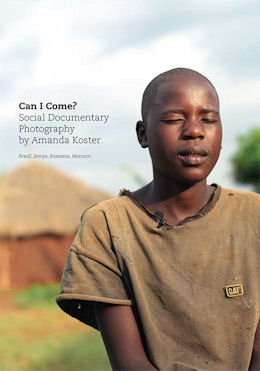

The new book of Amanda Koster, “Can I Come With You?” is being released September 16 at a special event at the Seattle Central Community College. Koster, whose photography based social media tours have attracted major media attention, and who used her participation in Landmark Education’s SELP program to expand her difference making projects, wrote the book not just to tell about her travels, but also to show others how easy it is to make a difference with nothing more than a camera and a pen.

The new book of Amanda Koster, “Can I Come With You?” is being released September 16 at a special event at the Seattle Central Community College. Koster, whose photography based social media tours have attracted major media attention, and who used her participation in Landmark Education’s SELP program to expand her difference making projects, wrote the book not just to tell about her travels, but also to show others how easy it is to make a difference with nothing more than a camera and a pen.

The book title was inspired by the many people who asked to come with Koster as she travelled the developing world taking illuminating photographs of other cultures. Her tours evolved out of these requests.

ReveNews recently interviewed Koster about the book, her career and how she became involved with social awarness tours. Parts of this interview appear below.

Altered Vision: Salaam Garage Gives Voice to Positive Content on Developing Nations

by Angel Djambazov

Photos have power. They can entertain, document, convey emotion, and form opinion. Without context the person looking at the photo may come away with emotions unintended by the photographer. Thus the beauty of art. Given context, photos can put a face to a tragedy that might otherwise simply be a distant statistic. That’s the power of the medium. Seattle photographer Amanda Koster believes in the transformative ability of photos. It is that belief that fuels the business of her company with a quirky name: Salaam Garage.

I sat down with her to learn more about Salaam Garage.

How did you get started in photography?

I ended up in photography while studying anthropology. I thought that developing strong photo essays would enhance my anthropology research projects. As I took the courses I found myself falling completely and madly in love with photography. I did finish my anthropology degree but I had decided that photography was where I really wanted to get involved because I wanted to have hands-on direct interaction with people.

I remember when I was little I saw a commercial of a photojournalist on TV. What’s funny is that it was a Tide commercial where the actor was purposefully crouching on the side of the street taking pictures when a car drove by and drenched her in mud. Of course Tide got all the mud out. But I thought to myself, wow that looks like a really cool job.

What helped shape the tone of your photography?

What helped shape the tone of your photography?

Immediately after I graduated I took a trip to eastern Africa, heading to Tanzania, Eritrea, and Ethiopia. I took a bunch of pictures while I was there. It was really early in my photo career and I wasn’t very good since I was still learning the craft. When I returned home I showed people my photos.There was one specifically I keep thinking about, of an Ethiopian kid on the side of the road selling bananas. People kept looking at the picture and asking me if I was sure I was really in Ethiopia. Because the kid wasn’t starving to death and in the background there wasn’t a desert.

And I thought to myself, wow, how powerful photography can be and how powerful telling a story along with photography can be. What would’ve happened if I didn’t have those pictures when I tell a person about my trip? Maybe the only pictures they’ve seen to that point were those made famous by Sebastião Salgado of starving kids being weighed on grain scales in the desert during the famine in Ethiopia in the 1980s. Are those the kids they would imagine I had seen on my trip? It was then I realized this is what I’m going to do, take pictures of what the world is really like versus all the pictures you see in various magazines.

How did dealing with cultural stereotypes impact your work?

I had a friend who is Ethiopian and I worked at her family’s Ethiopian restaurant as a waitress. The dumb joke I heard over and over again was, “Oh, Ethiopian restaurant? Better go there full.”

Those attitudes frustrated me. In my photography I want to show what the real place is like. I’ve never had much of an interest in bringing back pictures solely of horror stories, the kind people have seen over and over again. Because I feel that no one sees that anymore. We’ve grown immune to it. Numb to it. I mean with those stereotypes what good would it do to bring back photos of starving kids in Ethiopia? Let me bring back something that people haven’t seen before.

Why did you start Salaam Garage?

The reason I started Salaam Garage is because I had been doing photography work with NGOs for about a decade on different kinds of human rights and women’s rights projects. People kept asking me when they heard about my international projects, “Can I come with you?” Eventually I decided to put together a tour as a total experiment.

I identified an NGO called Vatsalya, who was doing work getting kids off the streets in India. These efforts involve child prostitutes or those at high risk for HIV infection. Vatsalya helps by placing them into an orphanage where they can learn various vocational skills in a safe environment. Vatsalya is Indian run and Indian founded, which was very important to me because I wanted to support a local group that understood the culture. I contacted the founder, Jaimala, who thought it was a great idea and helped organize things.

What I didn’t want was to be the tour guide with the visor and the whistle and the white sneakers. Instead we just quietly worked around Rajasthan India, a small group of people traveling the neighborhoods and back alleys. That’s what I want to see and that’s the way I work as a photographer. I don’t want to just see the market. I want to see the farm where they grow food; I want to see the alleys where they make stuff. I want to see where the people live.

What do you hope to accomplish with the content generated by Salaam Garage?

People are creating content all the time, literally vomiting content everywhere online in the form of blogs, podcasts, and viral video. What would happen if all that content creation was harnessed? What would happen if some of that content is actually out there to help make a positive impact in this world?

What if instead of some viral video of someone dancing in their underwear, people were posting interviews from the streets in India. Show a kid who is making it; an orphan who is now learning spelling and has a new outlook on life. There are people out there surviving homelessness, HIV-AIDS, child prostitution. Why not let some of those positive survival stories slide into all the content creation you see in places like Myspace.

What about people who want to create content but are concerned they are not professionals?

I don’t think being a professional makes any difference. Lots of people read magazines like National Geographic that are so over produced that people don’t find any kind of personal connection to the stories. The highly over produced content traditional media creates is so many layers removed from reality that it makes people feel they are unable to do anything about the subjects covered. And it’s simply not true.

Much like that first picture of the Ethiopian boy I mentioned earlier, anybody can go take a picture, show it and have it have a huge impact on the audience. When I took that picture I was not a good photographer. At that point like 80% of my pictures did not come out. Yet that photo still made an impact on my family and community.

How does the kind of content you want to create differ from mainstream media?

If you search mainstream media and try to find out information on India, aside from tourism you will find two main topics: articles about the booming economy focusing on the IT and a growing middle-class; or articles about the poverty, disease, and the homeless children. Rarely will you find stories about people overcoming these challenges facing them.

For example I went to Kenya and I did a project called AIDS is Knocking. It was conceived as a documentary about AIDS orphans and widows. I worked with a NGO in a community with a 38% infection rate, one highest infection rates of AIDS in the world. The problem with statistics is that they don’t have a face. During my work on AIDS is Knocking I kept hearing the statistic that 11 million children were orphaned due to the AIDS epidemic. What do 11 million orphans look like? Statistics don’t help people wrap their heads around the reality of a problem. I thought to myself let me find just one of those 11 million orphans, get to know them and tell their story.

In my case I found Caxton who was the oldest person in his family at 15 years old. Every day he worked on the farm growing his maze and his millet and he went to school. The next day he goes out and does it again. And you know, he is making it. For me the goal is to get to know one person, one story, hear the real story of their life, where they live, what they dream about, what they look like. These orphans do normal things in their daily life. They play, go to school and do their freakin’ homework. A life profile has far more of an impact on the audience than just saying the statistics of 11 million orphans over and over again.

Once I was asked to speak at Harborview Medical Center for this big conference on infectious disease. When I was first asked to present AIDS is Knocking, my first thought was I don’t know anything about infectious disease, I am a photographer. The conference featured PowerPoint after PowerPoint with lines going up and lines going down, numbers everywhere. When at last it was my turn everybody in the room was totally exhausted, hungry, and eager to go to the bar. I played the video to audience of Caxton and everybody was really quiet. Then I showed some photo slides when suddenly the conference organizer interrupted me, stood up and said to everybody, “Do you realize this is the first picture of a person we’ve seen all weekend?” There was dead silence. I mean, this is an infectious disease conference and all they were looking at were numbers and pictures of the disease but not of the people. They were that far removed. I thought that was a powerful lesson.

What is the future Salaam Garage?

I’m taking my time setting up more trips. I want to do it right. I’m not in any hurry for rapid growth. What I would like to see happen is for us to coordinate with schools in order to provide scholarships for people to go on these trips who otherwise couldn’t afford to participate. I would like to get some kind of corporate responsibility sponsorship as well. I am also releasing a new book about my experiences called Can I Come with You? It will be released on September 18 of this year. The book is available through the publisher Bennett and Hastings.

What advice would you give travelers who are thinking about doing this on their own?

I would say do as much preproduction as you can. In essence that is a big component of what Salaam Garage takes care of. Connect with people in the country you are visiting and try to let them know your intentions. That’s the most important thing to me is to be absolutely transparent with your intentions.

Do not go in there with ulterior motives. Do exactly what you said you were going to do. Be honest and realistic with yourself. Don’t think you’ll have an exhibit that’s going to travel the world the next day after you return. Expect when you show up things not to happen way you thought they were going to go. Be patient. In this country we’re used to having an Internet connection 24/7 and used to being in constant communication. There may be places where it might take a week to get information you really need. So well be prepared.

If you’re really there to make a difference, listen to what the people tell you, to what they need and to what will make a difference in their lives. Don’t make the trip about yourself; just be the medium for their story. To see this interview in its original form, go to the ReveNews website.