This story explores the work being done by Marnie Gustavson, a former Landmark staff member, to make a real and lasting difference in the quality of Afghan communities.

by Barbara Castleton

Lively and tuneful music videos from Jawad Sharif or Aryana Sayeed give little hint of the Gordian Knot that is modern life in Afghanistan. For over 150 years, bouncing from positions of power to pawn, Afghanistan has faced colonizers and wrestled with tyrants. The result is a cultural, political conundrum that the Afghani people negotiate every day as they struggle to carve a viable nation out of former battlefields, rugged mountain ranges, arid regions, damaged cities, and peoples with a long history of enmity.

Lively and tuneful music videos from Jawad Sharif or Aryana Sayeed give little hint of the Gordian Knot that is modern life in Afghanistan. For over 150 years, bouncing from positions of power to pawn, Afghanistan has faced colonizers and wrestled with tyrants. The result is a cultural, political conundrum that the Afghani people negotiate every day as they struggle to carve a viable nation out of former battlefields, rugged mountain ranges, arid regions, damaged cities, and peoples with a long history of enmity.

Into this ambiguity, non-profit organizations have gathered and initiated campaigns with an eye to fixing what doesn’t work in this complex nation. A study of these organizations, foundations, and associations, may well become a series of revealing PhD dissertations in the future, but one woman is already observing, analyzing, and rethinking that outreach model – providing long term social and community benefit to thousands in the process.

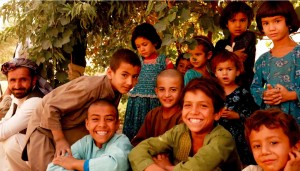

Memory drew Marnie Gustavson back to Afghanistan after decades away. As a child she had reveled in the sights, sounds, tastes, and people she met living among the myriad clans within the Pashtun, Uzbek, and Tajik tribes. From age 9 to 13, Marnie, her sisters Fran and Ruth, and her mother and father were students and residents of a land and culture thousands of miles from their homeland. Marnie learned Dari, attended school, made friends, and grew to love the country and the people.

Later on, back in the United States, she watched, read, and heard how Afghanistan was torn by successions of military clashes that arrived like deadly, malevolent storms. Any timeline of Afghanistan over the past 50 years will be punctuated with internal conflicts and external invasions. Mourning the dead has become a national pastime throughout this nation of over 30 million people, and it is widely known as a place dangerous for foreigners and citizens alike. Yet, like the call of a muezzin from a neighborhood mosque, Afghanistan continued to reach out to Marnie.

So, ten years ago, after a varied career that included time spent as a consultant, an at-risk youth counselor, and a Landmark staff person, Marnie chose to return. Initially, those periodic sojourns were contract driven, as she worked for various organizations trying to mediate a path within the maze of cultural, international, military, and social barriers. Along the way, she noted how many programs, campaigns, and organizations had fallen by the wayside in Afghanistan as funding was diverted, misspent, or drained without measurable results.

So, ten years ago, after a varied career that included time spent as a consultant, an at-risk youth counselor, and a Landmark staff person, Marnie chose to return. Initially, those periodic sojourns were contract driven, as she worked for various organizations trying to mediate a path within the maze of cultural, international, military, and social barriers. Along the way, she noted how many programs, campaigns, and organizations had fallen by the wayside in Afghanistan as funding was diverted, misspent, or drained without measurable results.

One organization, Parsa of Afghanistan, launched in 1996 under the leadership of Mary MacMakin, focused its efforts on widows and orphans, and suffered regularly from a lack of funding. Mary asked Marnie to join her and guide Parsa as it expanded into a broader range of needed programs. Marnie Gustavson brought years of experience and skills to Parsa, plus an organizational quiver replete with a singular educational and facilitating style, specifically the functional and enrolling training received at Landmark.

Fascinated by the development challenges inherent in the culture and the landscape, Marnie set out to open up the landscape through conversation rather than expert driven instruction. And, because literacy is limited in a country where schooling has been interrupted by warfare and a dearth of trained teachers, where girls have long been restricted or denied education and where resources are few, she utilized another tool–conversation. Why? Because through conversation, one can gather information, clarify goals, organize strategies, and analyze results.

“In some ways,” says Marnie, “you have to think your way into an illiterate person’s world. It is very difficult for a person with a Western mindset to do this.” She explains that people from developed nations make all manner of assumptions about an uneducated person’s experience, understanding, and beliefs. “Their [the illiterate person’s] resourcefulness is limited,” she observes, and their lives are often lived entirely in areas that are very, very remote. “Just imagine a life on a mountain with no change but the seasons, no stimulus, and no variation outside of a narrow existence.”

The similarity between all peoples is that each of us maps what we see onto our own experience. In the US and other developed nations, individual people experience life through a lens trained on a variety of locations, communities, changes, and opportunities. Not so in Afghanistan.

The work then, does not begin with a program to be implemented. It begins with discussion. “Instead of trying to do a program, I am opening it up based on the conversation I am having,” says Marnie. “My overarching program is ‘Healthy Afghan Communities’. We go in to ask, “What do you think a healthy Afghan community looks like? Is your community healthy?” The answers are yes and no, respectively. Yes, a healthy community offers education, infrastructure, enough food, jobs, health care, and opportunities. No, because our children aren’t being educated, there are no jobs, and the city and town governments and structures are riddled with corruption.

The work then, does not begin with a program to be implemented. It begins with discussion. “Instead of trying to do a program, I am opening it up based on the conversation I am having,” says Marnie. “My overarching program is ‘Healthy Afghan Communities’. We go in to ask, “What do you think a healthy Afghan community looks like? Is your community healthy?” The answers are yes and no, respectively. Yes, a healthy community offers education, infrastructure, enough food, jobs, health care, and opportunities. No, because our children aren’t being educated, there are no jobs, and the city and town governments and structures are riddled with corruption.

Throwing money at those problems doesn’t work, a lesson societies have had to learn over and over. Marnie and the team she has trained are not about money; they are about empowerment. The best way to explain is to tell a story.

Through its Trade Afghan Economic Program for Women, Parsa has enabled Afghan women in several sites across the country to learn and produce arts and crafts for sale in the local bazaars and souks. Regional centers provide space and instruction, giving the women a location outside their home in which to work, build community, learn marketing strategies, and produce goods.

In one such center, Yasin Farid, the National Director of Parsa, envisioned a vegetable garden that would provide nutritional options for the staff when they came on regular visits and the women as they worked. He asked the ladies to see to the garden in his absence so that it would thrive. Somehow, it never got seen to. So, Yasin changed the conversation. “If I provide the seed and teach you how to garden, would you like to take the vegetables home to your families and maybe sell the extra in the market?”

Initially, 15 or so women worked at the center and helped out in the garden. That number has double, trebled, and quadrupled over time and across distances with hundreds of women nationwide now gaining substantial income from their crafts and from selling vegetables from the gardens that have grown exponentially. In fact, many of the ladies are making $100 per month, the equivalent of $2000 in America. That simple change in conversation has also mean healthier families as children benefit from a higher level of nutrition.

Beyond those measurable benefits, the women have learned a great deal about 1) small plot farming, 2) how to divide labor and be accountable to a group, 3) balancing the needs of a family with the need for additional income, 4) marketing at a local and national level, 5) budgeting and saving, 6) and, crucially, how to model a ‘can do’ attitude for the next generation. These women have learned that skills and focused energy can help them achieve a lifestyle they believed beyond their reach.

While enabling women to earn money and feed their families is critical, the gender-related social issues faced by women in Afghanistan are literally crippling. Parsa works with five NGOs responsible for 30 battered women’s shelters across the country, training staff on how to deal with abused wives and daughters. The biggest obstacle for women in Afghanistan is that male to female violence is socially condoned, creating a situation easily perpetuated in communities where the teachings of Islam are distorted or manipulated.

The question was, how to approach the subject of abuse, how to effectively mitigate its entrenchment, and how to manage all of this without creating additional risk? Parsa took its inspiration and conversation directly from the Qur’an, the holy book of the Muslim religion. In its pages were all the lessons necessary, and by teaching women their personal rights based on the chapters and verses of the Qur’an itself, Parsa launched one of its most successful training programs yet. “I focus on the conversation I want to see manifest,” says Marnie, which in this case meant creating a healthy community one woman at a time.

Over and over, Marnie reminds me that “I have a stand for creating healthy Afghan communities, which is not the same as ‘fixing Afghanistan’. We initiate a conversation, provide support, and a willing ear. We work on programs that may start locally, but which are designed to go national. These programs, growing throughout the country, tie the regions together.” These sentiments could easily have come from the classroom notes and experiences of the Self-Expression and Leadership Program cohort that Marnie considers the crux of her personal philosophy and organizational strategies.

With that training as a touchstone, the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts of Afghanistan have gone from floundering to flourishing, now numbering over 1500. Parsa initiated a movement that soon grew the number of scout masters available in Bamiyan, Chagcharran, and Kabul from a handful to a numerous and willing contingent. Using the recognized enticement of the scout merit badge system, police officers in each location were enrolled in teaching the scouts the basics of fire safety, citizenship, and first aid.

Gradually, the scouts and their scout masters extended their reach beyond the classroom and into the community. The scouts in Bamiyan took on garbage collection in the area around the largest hotel. Week after week, they stooped and grabbed, filling dozens of bags with the detritus left by careless staff and visitors.

It didn’t take long for the scouts to start seeing the entry way of the hotel as the origin of most of the trash. The scouts complained to their scout master and eventually, the issue reached Yasin Farid. He turned the question around, “Call the owner and tell her what you have seen.” As it happens, the owner of the hotel is Dr. Sima Samar, human rights advocate and winner of the Profiles in Courage award.

Perhaps because it is Afghanistan and not Washington D. C., the scouts were actually able to reach Dr. Samar directly. They shared the tale of their garbage collection project and how the hotel wasn’t being a good citizen. They went so far as to suggest that she get her hotel staff to clean up their act. And, so, it came to pass.

The essence of this simple interchange may be lost on those who haven’t lived and worked in a third world nation, but, Marnie explains it this way, “Our kids are a recognized, valued community in the town. The youth are stepping up. This year they are funded to do ‘Messengers of Peace’. What would peace look like in different environments they are familiar with? It will be the youth who envision that and then create it. They have such strong voices, not because they have been funded, but because they have been empowered. “

Find out more at the Afghanistand Parsa website.

5 comments

The work Marnie Gustavson and her staff are doing is so powerful. As a fellow Self Expression and Leadership leader I know first hand the power of speaking an intention and creating a project from nothing. Marnie is a remarkable woman and is doing just that. Her work is transforming a country! She is an inspiration to say the least and a model for what is possible when you put into action your intention for the world.

Well said, Heide!

Wonderful story that displays how listening and altering a conversation can produce unexpected results. Thanks.

Powerful story. Marnie is leading resurgent Afghanistan, where we have peace, happiness and harmony once again. Hats off to you. You are an inspiration.

I am always interesting reading all about this country. Never-ending conflict and health issue is one the most of interesting issue of Afghan to be discussed.

http://scholarshipdesk.com/2015-oxford-centre-for-islamic-studies-ocis-scholarships-uk/